Sixers can't just be normal

(Never Too Much podcast: Brooklyn and the best of Kyrie, Pau Gasol retires, Kelly brags about being flown to Orlando.)

If you’re a Sixers fan, fine. Continue gnawing on your elbow.

The rest of us? I think we’re supposed to leave Ben Simmons and those Sixers alone until they actually do something.

Each side dropped its hand last month, thinking it would be enough to pull the pot and end the evening. Simmons’ reps, Rich Paul and co., are intent on playing by their own rules and for this, they rule. As Kyle Neubeck of Philly Voice opine-de-re-layed:

Fair or unfair to Paul — and there’s an argument he draws more heat than any non-player in the league right now — there are people at the team and league level who see this as the continuation of a pattern with his clients, characterized by one league source as throwing stuff at the wall and hoping something sticks. The expectation is that there will be another attention-seeking headline generated in the days to come as they assess their options of what to do next.

I’d guess they’re probably going to keep doing what they’re supposed to do.

Neubeck reported late Tuesday that Paul and co. sought to recoup the fines the Sixers docked Simmons, $360,000 and counting after an exhibition loss to the Raptors on Monday that I sincerely hope you did not watch.

The Sixers’ front office is full of corporate cologne and cufflinks plus what’s left of Daryl Morey after he out-foxed zero hounds. Rooting against Ben, in this instance, isn’t an option. Especially when the payout — finally, a balanced lineup around Joel Embiid — aligns with our interest in seeing a player push these puddles around.

The Sixers’ front office is so full of men used to getting what they want that Morey will absolutely follow through on orders to burn the crops ahead of retreat. Nobody asked for the bunker Morey dug, and Simmons’ side has a duty as legal reps to fight for the money at stake in spite of long odds of recuperation.

Everyone earned a Ben Simmons opinion during his indifferent single season at LSU, Simmons was either the hero that saw the forest for the trees or the straw that broke the layman’s back. Uncommon inspire conversations you think you have to shout through.

Simmons is worth shouting over, and the NBA hasn’t had a holdout in ages. It is normal to gargle over someone this unprecedented, doing something we haven’t seen since 1994.

Maximum extensions are a two-way street, they provide the most money possible to a player and they fasten the most cash possible to a top-flight asset, making it resoundingly easier for GMs to demand ready-to-play-tonight talent in return.

Sam Presti was the first to roll with it, he couldn’t be happier that Paul George made a single-team request, and look what the Clippers had to pay to find George a new place to live. David Griffin, rather beleaguered, still nailed the Anthony Davis deal. These things can work for you if you don’t take them personally, or try to act like the smartest crank among 30.

Daryl Morey and the Sixers failed one and two and, now look, three. He and his bosses had to act like they’re different, which they are not. They couldn’t just trade Ben Simmons for Some Bullshit at Guard and give the generational center more room in the paint and his head coach a proper training camp.

Morey’s ostensible hope is cynical. Penalize Simmons until he breaks, corrupt a common team into relenting sometime past mid-December, bank on the NBA news cycle to help us forget September and October (and probably November) ever happened. Still not a wow.

Many things wow me, the layman. Basketball trades do not, because they’re sports.

Make a basketball trade, get back to sports.

1994

Jimmy Butler relented, so did James Harden. Ken Norman showed up to the Omni every night and put on his warmup jacket and sat at the end of Lenny Wilkens’ bench. Eric Bledsoe didn’t want to be there but he tried to show up to work the next day, because he wanted to be paid.

Free agents have sat out, the Cavs took a while to sign restricted free agent Tristan Thompson in 2015, the team pulled the same junk with Anderson Varejao and Sasha Pavlovic in Cleveland’s 2007-08 Eastern Conference title defense. Bison Dele was ready to pass on an entire season rather than sign with the team (the Clippers) glomming onto his Bird Rights, eventually making $27,164 (plus title share) with the 1996-97 Chicago Bulls.

Players have retired for religious reasons. Some guys walk away citing burnout and/or the trading of Paul Silas1. Some players set the record for most three-pointers ever made, retire, and then spend the next few years annoying us with comeback rumors.

Nobody’s given money back, not in a move I can find, in a bid for a trade. Losing a paycheck is a bridge too far, any trade demand with a GM who isn’t a weirdo can land a dealing partner plenty. Trade demands don’t usually get this far because nobody’s ever bowled with Daryl Morey before.

Rookies used to hold out, all the time, Jim Jackson waited until there was a month left in his rookie season to sign his first contract, and if you’d seen the 1992-93 Dallas Mavericks, you’d understand why.

Hold-outs haven’t existed 1994, a year before the NBA and its players’ union agreed on rookie scale contracts, deals which could be added to a capped-out payroll.

Prior to the 1995 draft, teams with a lottery pick to sign had to consider their capability of keeping an unhappy camper on the farm (Danny Ferry fled to Italy rather than play with the Clippers), and trim payroll ahead of an expected, probably record-breaking, rookie contract. Veteran cuts led directly to rookie hires, not a great scene.

The 1994 rookie class took full advantage, setting the bar at $100 million and holding out until they didn’t get it.

Agent Ron Grinker says that if [a draft pick] gets $100 million, “it’s going to cost other guys, those who will be renounced to make room. I believe that you should pay players who prove themselves. What we’re talking about now is paying one player four times more than what a franchise was worth 10 years ago.

“Why pay a rookie $100 million? Is that team going to be in the playoffs next season? Why not pay him in three years, when he proves what he can do?

Top overall pick Glenn Robinson’s agent got the ball stopping:

“I was asked about it, and I said that seemed to be the way the market is going,” [Charles] Tucker said. “I would say any No. 1 pick in any sport would have a chance to do it. Situations change every day.

“People tend to react to the singular impact of $100 million. A player can sign for four or five years for any number and no one says anything.

In backtracking, Tucker reduced everyone’s yearly take:

“Say ‘$100 million,’ and everyone jumps. They don’t look at the terms. For a contract to be worth that much, it would have to be over a long number of years.”

The No. 2 pick, Jason Kidd, signed a nine-year, $54 million deal a month ahead of training camp. Third selection Grant Hill inked an eight-year, $45 million contract at the start of camp, as did No. 4 pick Donyell Marshall with his $45 million deal.

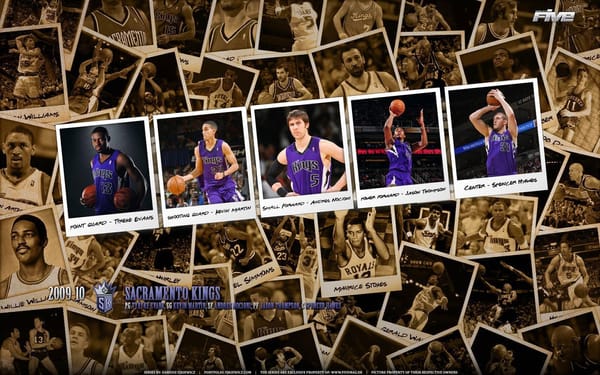

No. 6er Sharone Wright got six years and $18 million from the 76ers early, though No. 7 pick Lamond Murray had to hold out two weeks to get five-years and $13.5 million out of the L.A. Clippers. Eric Montross, 11-years, $20 million. The Sacramento Kings, as you’d guess, had the No. 8 pick, selecting Brian Grant, who held out a month before signing to be a Sacramento King for 13 years.

Grant threatened to play in Greece before signing a $29.33 million, 13-season, deal with the Kings. The thirteenth year of the contract was conditional, Brian had to play seven seasons to earn it.

Kings officials said Grant was expected to be in uniform for the final preseason game Sunday night against the Golden State Warriors.

“It will take Brian a little time to get adjusted to the level of competition in the NBA,” coach Garry St. Jean said. “His running and jumping abilities along with his strong skills on both sides of the ball indicate that he will be a strong player in this league for many years to come.”

Thirteen years, even. And of course the Kings gave him an opt-out clause after three seasons.

Grant helped Sacramento to its first playoff berth in a decade in 1996, missed most of the next year with injury, and left for Portland (and a seven-year, $63 million deal) in 1997. He asked for an opt-out clause from the Blazers after a three years, which Brian used to negotiate a sign-and-traded, seven-year, $86 million deal with the Miami Heat.

Robinson held out the second-longest right until the edge of the 1994-95 season, inking a ten-year, $68 million deal with Milwaukee:

“Both sides won,” said the team’s owner, Herb Kohl, a United States Senator from Wisconsin who is up for re-election Tuesday.

“Glenn Robinson has now got a pro career under way in a city that he wanted to play in with a very nice 10-year contract fully guaranteed. And for the Milwaukee Bucks, it’s wonderful to sign the No. 1 pick.”

Asked how the deal was reached after months of gridlock, Kohl said: “The season starts tomorrow. Glenn Robinson’s a basketball player. He wants to play basketball.”

The team was quiet ahead of Robinson’s absorption, signing Johnny Newman to a minimum deal (Newman later sign a three-year extension with a 400-percent yearly salary increase, huh) alongside a two-year, minimum contract to Marty Conlon (Conlon later sign a two-year extension at a thousand-percent increase, huh). Even after shedding salary, the Bucks couldn’t convince Robinson to come to camp.

When Big Dog suited up, only Juwan Howard remained unsigned. The No. 5 pick sat out seven Washington Bullets games before Chris Webber tried to create a superteam:

After much acrimony between his representative and the Bullets, Howard, the fifth pick in June’s draft, signed an 11-year deal worth $36.6 million.

Webber, acquired from the Golden State Warriors for forward Tom Gugliotta and first-round draft choices in 1996, 1998 and 2000, signed a one-year deal worth $2.08 million. Under the terms of their respective deals, both players could possibly leave Washington, Webber after one season and Howard after two, but fans didn't seem very concerned about the future.

Nah.

“We’ve never had anything this big in the 30 years I’ve owned the team,” said Bullets owner Abe Pollin, who in one day guaranteed millions to the two players.

Abe Pollin’s team won a championship 16 years before this statement, and this is back when 16 years only felt like 16 years.

“[…] Webber went public with his desire to play in Washington -- on the condition that he play with Howard.

“[Webber] and Juwan spoke, and, despite his situation, Juwan really liked the area,” Strickland said. “Juwan was a part of the appeal.”

Though Howard’s representatives downplayed Webber’s role in Howard agreement, Juwan submitted to a $1.3 million salary slot, lower than Lamond’s, for his rookie season. “A sticking point in negotiations” in exchange for an opt-out after two seasons, which sounds ridiculous until you realize that the Bullets only had to be negotiated down from three seasons.

Howard opted-out, of course, and eventually signed a seven-year, $105 million deal with the Bullets, making him the NBA’s second (SHAQ) $100-million signee.

BANG!

First four Pie albums. I’m telling you.

Other content upsetting you? Want to revenge-subscribe? I’ll take your revenge-subscribe.

Thank you for reading and listening!

Here is our first-ever footnote, which is by now fun to read out of context: